Relations

We often need to relate the elements of a set to those of another set or to other elements of the same set: take for example the equality relation among the elements of a given set. In working with the integers, we encounter relations such as "x is less than y" and "x is a factor of y". These relations can all be described by the following definition.

Definition 1.2.1 (Relation). Let A and B two nonempty sets, a relation indicated with ℜ is the subset ℜ ⊆ A x B

When A = B, we say that ℜ, is defined on A. Intuitively a relation ℜ in A is a law that to each element of a subset A (that could also be the whole A), associates one or more elements of A itself.

Instead of writing (a,b) ∈ ℜ, it is usually written a ℜ b.

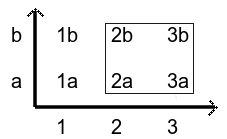

When we build up a set by choosing only some elements of a cartesian product we are creating a relation. Consider the following example given by the Cartesian product [a,b] x [1,3]:

By choosing some pairs of the cartesian product we obtain a subset (relation) like that enclosed in the blue frame ℜ= {(2a), (2b), (3a), (3b)}. The term relation is thus justified since we are relating the elements

Definition 1.2.2. Let A a set. A relation ℜ on A is a subset of A x A. If (a,b) ∈ ℜ then we write a ℜ b and we say that a is related with b through the relation ℜ.

Examples

the relation ≤, defined on ℕ.

the relation of being friend of, defined on a given group A of people.

the relation ℜ made by all pairs (a,b) di ℝ x ℝ such that a + b = 1: geometrically, this relation coincides with the line x + y = 1 of the plane ℝ x ℝ.

There exists multiple relations which can be chategorized based on the the property they satisfy

Functional relations

Ordering relations

Equivalence relations

Functional relations are simply functions, thus a relation in which the second element is univocally determined by the first: e.g. in the pair (a,b) the element b is unique with respect to a.

Equivalence relation

Definition 1.2.3. An equivalence relation indicated with the symbol ∼ (to be read "equivalent to", from left to right) is a binary relation on a set A satisfying the following conditions:

x ∼ x ∀x ∈ A Reflexive Property

x ~ y implies y ~ x ∀x,y ∈ A Symmetric Property

x ∼ y and y ~ z imply x ∼ z ∀x,y,z ∈ A Transitive Property.

Two element that satisfy the conditions above are said equivalent for the relation ∼: the symmetric property allows us to disregard the order in which the elements appear in the relation.

1.2.4 Example. Let A = {2,3,4} and B = {2,6,8,12} and let R be the "divides" relation from A to B: For all (x,y) ∈ A x B,

x R y ⇐⇒ x | y x divides y

We have R = {(2,2), (2,6), (2,8), (2,12), (3,6), (3,12), (4,8), (4,12), (6.12)}. The relation R on set ℕ, defined by "x divides y" for all x,y ∈ ℕ is a transitive relation because if x divides y and y divides z, then x divides z. ■

Definition 1.2.4. If A is a set and if ~ is an equivalence relation on A, then the equivalence class in A is the subset of all those elements of A which are related to a by the relation ~. Usually it is indicated by [x]∼ or {x}∼. Symbolically

[a] = {x ∈ A | a ~ x}

Observe that equivalence class is never empty as a ∈ [a].

Given an equivalence relation R, the set I can be divided into classes, known as equivalence classes which groups equivalent element in a same class.

The set of equivalence classes under ∼ is called the quotient set of A with respect to ∼; it is usually indicated as A / ∼. An equivalence relation on a set induces a partition on it, and any partition induces an equivalence relation.

to denote an equivalence relation the symbol ~, is frequently employed. Thus (x, y) ∈ ℜ, can be expressed using the notation x ~ y.

1.2.5 Example. Let A {1,2,3,4} and R = {(1,1), (2,2), (2,4), (3,3), (4,2),(4,4)} be a binary relation on A. Note that R is reflexive, symmetric and transitive hence an equivalence relation. ■

1.2.5 bis Examples of equivalence relations

The equality relation defined on a set A: a = b

The relation of having the same age in a group of people;

The relation ρ defined on a set A, declaring a relation among all elements of the set that is a ρ b ∀a,b ∈ A.

Considering the citizens of a country, the relation "lives in the same city" is an equivalence relations: it is reflexive, symmetric and transitive.

In ℕ, the relation "is greater or equal to" is not of equivalence: is reflexive and transitive, but not symmetric.

Considering a family, the relation "is brother of", is of equivalence: indeed it is reflexive, symmetric and transitive.

Considering a family, the relation "He is father of", is not an equivalence relation: it is not reflexive nor symmetric nor transitive.

The relation P of parallelism between lines is an equivalence relation, r P s means "the line r is parallel to the line s.

Definition 1.2.6. Let ~ an equivalence relation defined on a set A. We denote as [a] (or also ā) the set containing all and only the elements equivalent to an element a of A and call it equivalence class modulo ~. In symbols

[a] := {b ∈ A | b ~ a}

In example 1.2.5 a) the equality relation is an equivalence relation; The equivalence classes are all singletons (i.e. subsets made of single elements). In example 1.2.5 b) an equivalence class contains all people with same age and each class can be labeled by a number corresponding to an age. In example 1.2.5 c) there is only a single equivalence class that coincides with set A itself.

The following proposition illustrates that is possible to pass from an equality of equivalence classes to an equivalence relations between elements of the set.

Theorem 1.2.7. Let ρ be an equivalence relation on a set A. Then

[a] = [b] ⇐⇒ a ρ b

Proof. Let [a] = [b]. By the reflexive property of ρ, ∀ b ∈ A we have b ρ b thus b ∈ [b]. By hypothesis [a] = [b], hence b ∈ A from which by definition of equivalence class b ρ a and by symmetry a ρ b.

Conversely, suppose that a ρ b, we shall show the double inclusion [a] ⊆ [b] and [b] ⊆ [a]. Let c ∈ [a]. Then a ρ c which along to b ρ a imply by transitivity b ρ c, thus (by definition of [b]), c ∈ [b]. We just proved that [a] ⊆ [b]. To prove the other inclusion is analogous exchanging the roles of a and b. Thus [a] = [b]. □

Definition 1.2.8. Let ρ be an equivalence relation defined on a set A. We define the quotient set of A with respect to ρ, and we indicate it as A / ρ, the set of all equivalence classes modulo ρ. In symbols

A/ρ := {[a] | a ∈ A}

The previous definition states that equivalent elements a in A are transformed in a single element, [a] of A/ρ.

Partitions

Definition 1.2.9. A partition of a set A is a set of pairwise disjoint non-empty subsets Aα called parts (or members) of A such that

Uα Aα = A (the parts cover A entirely)

Aα ∩ Aβ ≠ ∅ ⇐⇒ Aα = Aβ (either the parts coincide or are disjoint)

For example the sets

{2,3}, {1,5}, {4}

For a partition of the set {1,2,4,5}.

The two subsets of ℤ, of even and odd integers form a partition of ℤ.

Theorem 1.2.10. Let ρ be an equivalence relation on A. The equivalence classes of A modulo ρ make a partition of A.

Proof. (1) They cover A: indeed, since a ρ a for every a ∈ A, every a ∈ A, belongs to its equivalence class. (2) The equivalence classes either coincide or are disjoint: let z ∈ [a] ⋓ [b], i.e. [a] and [b] not disjoint. Then z ρ a and z ρ b, from which, by symmetry and transitivity, a ρ b. By Proposition 1.2.9, [a] = [b], that is the two classes coincide.□

Theorem 1.2.11. Every partition of a set A determines on A an equivalence relation, with the parts of the partition the equivalence classes.

Proof. Indicating with Aα the subsets of the partition, it suffices to define the following relation

a ρ b, ⇐⇒ ∃Aα | a,b ∈ Aα

which is an equivalence relation, whose classes are the parts Aα. □

Definition 1.2.12. A relation ρ defined on a set A is said antisymmetric if

a ρ b, b ρ a ⇒ a = b

Composition of relation

Let A,B and C be ordinary sets. Let R be a relation from A to B, and let S be a relation from B to C. The composition of R and S is a new relation (called composite relation) denoted R ∘ S and defined by

R ∘ S = {(a,c) |(a,b) ∈ R, (b,c) ∈ S, a ∈ A, b ∈ B, c ∈ C}

The composition of two relation can be extended to the composition of n relations as R1 ∘ R2 ∘ ... ∘ Rn. Since composition operation is associative, that is, (R1 ∘ R2) ∘ R3 = R1 ∘ (R2 ∘ R3), we can drop the parentheses and simply write R1 ∘ R2 ∘ R3.